DEDICATED TO PRESERVATION, RESTORATION & REVITALIZATION OF THE MOSHASSUCK RIVER

Your Bird Story Podcast Episode

(click to listen on Spotify)

Greg Gerritt for PVDeye January 3 2024

The name Moshassuck means "where the moose drink" in reference to the wide flood plains that were pockmarked with the small wetlands filled with the vegetation moose love to eat. Moose would find not Rhode Island particularly hospitable today, due to the draining of the wetlands and the rising temperatures of the current pollution-induced climate catastrophe that allow moose parasites to thrive, but during the Little Ice Age (1300AD to 1850AD) this was moose country.

The Moshassuck River has been dammed and polluted at least since 1675 and probably even earlier, making pollution history among the longest in what is now the USA. It is a small river, less than ten miles long, running from the Limerock section of Lincoln to the tidewater in Providence where it joins with the Woonasquatucket River to form the Great Salt or as it is currently known, the Providence River. In addition to being short, it is narrow and has a watershed of only twenty three square miles. Small as it is, along the banks of the lower Moshassuck is where Roger Williams founded the first settler colony in Rhode Island, near a spring below what is now College Hill. From its very beginnings in that colony, the Moshassuck was used as a sewer, with human excrement pouring in from houses along the river and nearby.

The estuary where the Moshassuck River reaches the sea in what is now downtown Providence was once an incredibly rich ecosystem with abundant fish, shellfish, and birds. But as Providence grew up around it, every sort of pollution poured into the Moshassuck. At its heyday in the industrial revolution, around the turn of the twentieth century, more than a hundred mills lined its banks pouring out dyes from textile mills, as well as chemicals and heavy metals from industrial plants making machinery. At least seven dams were built along the river, the tallest at Barney Pond in Lincoln, at the edge of what is now Lincoln Woods State Park.

Turning the lower five miles of the Mosassuck into a canal, from southern Lincoln to the tidewater, in 1829, only added to the damage to the river. The Blackstone canal, running from Worcester to Providence until the railroads put it out of business in 1846, cut through the lower Moshassuck instead of along the Blackstone River to Pawtucket. This route was chosen because the lower Blackstone has so many larger waterfalls it was impossible to put a canal through with the construction technology of the time, and because there was not enough water in the system to manage the locks needed to raise and lower the barges that the steep falls would have required.

With the coming of the railroad, the closing of the canal meant that there was more water available to run the mills, and starting in 1847, as new mills were built, new mill housing sprang up along the Moshassuck. The industrial pollution and the volume of household sewage in the river increased dramatically, and what little life left in the lower river almost disappeared. By the 1920’s, some of the communities had built sewage treatment plants, and the mills started closing, but the water quality was still so bad that almost no one got close to the lower river, and almost all the construction was designed to face away from the river in an attempt to wall it off. In fact, the lower Moshassuck was the site of several cholera outbreaks in the nineteenth century, until the building of the Fields Point sewage treatment pushed the pollution further down the Bay.

The Clean Water Act of the early 1970’s was finally the first glimmer of hope for the lower Moshassuck since the 1600s, but even the passage of legislation did not change much at first. Eventually the industrial pollution was much reduced, and the towns now have better sewage treatment plants, but here again history has a grip: the old sewer systems still combine rainwater and sewage, and when there’s heavy rain, some raw sewage still flows into the river.

The dawn of the twenty-first century brought significant change when the EPA mandated that Rhode Island address combined overflow sewage. A billion dollar Combined Sewage Overflow project was begun so that the rainy day sewage can be captured and treated at the sewage treatment plants instead of running into the rivers. Phase One and Phase Two are now completed. But alas, it is going to take Phase Three to capture the raw sewage that continues to flow into the Moshassuck River, and while that phase has started, it will be at least two more years before completion.

Phase Three includes building a 3 mile tunnel from the Moshassuck River right on the border between Pawtucket and Providence all the way under Pawtucket to the Bucklin Point Sewage Treatment Plant in East Providence. When this work is finally done, more than 90% of the rainwater and sewage that flows into the upper Moshassuck will be captured and treated. The lower Moshassuck should become much cleaner. The river will not be swimmable or fishable, as the Clean Water Act specifies, but it will be much less dangerous to the community and much more amenable to the creatures that rely on the river. We can only hope that in 2025, when the project is complete, the restoration of the Moshassuck can begin and the lower-income communities along the lower river will start to see the benefits that have already come to other areas that the Narragansett Bay Commission sewage system covers.

Greg Gerritt for PVDeye November 8 2023

The people who lived along the Moshassuck River before the English so rudely removed them...

…lived in an environment of tremendous richness, a richness that sustained their communities and cultures. We honor the people and cultures who preceded us in this place, and rue the damage that the Europeans did to the communities and ecosystems of this place and to all of Turtle Island. The name Moshassuck means where the moose drink in reference to the wide flood plains that were pockmarked with the small wetlands filled with the vegetation moose love to eat. I doubt moose would find Rhode Island particularly hospitable today due to the draining of the wetlands and the rising temperatures of the current pollution induced climate catastrophe that allow moose parasites to thrive, but during the Little Ice Age (1300 to 1850) this was moose country.

The Moshassuck River has been dammed and polluted at least since 1675 and probably even earlier, making its pollution history among the longest in what is now the USA. It is a small river, less than 10 miles long running from the Limerock section of Lincoln to the tidewater in Providence where it joins with the Woonasquatucket River to form the Great Salt or as it is currently known, the Providence River. In addition to being short, it is rather narrow and has a watershed of only 23 square miles. Small as it is it was along the banks of the lower Moshassuck that Roger Williams founded the first settler colony in Rhode Island near a spring below what is now called College Hill. And in that colony it was used as a sewer with human excrement pouring in from houses along the river and nearby from its very beginnings.

The estuary where the Moshassuck River reaches the sea in what is now downtown Providence was once an incredibly rich ecosystem with abundant fish, shellfish, and birds. But as Providence grew up around it, every sort of damage that human beings have figured out how to do to a river since the beginnings of civilization was done to the Moshassuck. At its heyday in the industrial revolution more than 100 mills lined its banks pouring in dyes from textile mills, as well as chemicals and heavy metals from industrial plants making machinery and dyes for textile mills. At least 7 dams were built along the river, the tallest at Barney Pond in Lincoln at the edge of what is now Lincoln Woods State Park.

Adding to the damage to the Moshassuck was that the lower 5 miles of the river, from southern Lincoln to the tidewater was turned into a canal in 1829. The Blackstone canal that ran from Worcester to Providence until the railroads put it out of business in 1846 ran through the lower Moshassuck instead of along the Blackstone River to Pawtucket because the lower Blackstone has so many larger waterfalls that it was impossible to put a canal through with the construction technology of the time and because there was not enough water in the system to manage the locks needed to raise and lower the barges that the steep falls would have required. It would take another article to explain how the route through the Moshassuck developed.

The closing of the canal meant that there was more water available to run the mills, and starting in 1847 new mill villages sprang up along the Moshassuck and new mills were built. The industrial pollution, and the amount of household sewage in the river increased dramatically, and what little life there was in the lower river almost disappeared. By the 1920’s some of the communities had built sewage treatment plants, and the mills started closing, but the water quality was still so bad that almost no one even got close to the lower river and almost all the construction was designed to face away from the river walling it off. In fact the lower Moshassuck was the site of several cholera outbreaks in the 19th Century until the building of the Fields Point sewage treatment pushed the pollution further down the Bay.

The Clean Water Act of the early 1970’s was the first glimmer of hope for the lower Moshassuck since the 1600s, but even the passage of the Act did not change much quickly. Eventually the industrial pollution was much reduced, and the towns now have better sewage treatment plants but the old sewer systems still combine rainwater and sewage when there are large rain events and in big rain storms raw sewage still flows into the river. The dawn of the 21st Century brought another big change. The EPA cracked down on Rhode Island and the billion dollar Combined Sewage Overflow project was begun so that the rainy day sewage could be captured and treated at the sewage treatment plants instead of running into the rivers. Phase one and Phase two are now completed and in much of the Providence area more tan 90% of the sewage that flowed into the rivers and Narragansett Bay on rainy days is now captured and treated, meaning the Bay is much cleaner. But alas, it is going to take Phase 3 to capture the raw sewage that flows into the Moshassuck River, and while that has started it will be at least 2 more years. Phase 3 is building a tunnel from the Moshassuck River right on the border between Pawtucket and Providence all the way across Pawtucket to the Bucklin Point Sewage Treatment Plant in East Providence. When this is finally done more than 90% of the rainy day sewage that flows into the Moshassuck will be captured and treated. It is expected that the lower Moshassuck will become much cleaner. Not swimmable fishable the way the Clean Water Act calls for, but much less dangerous to the community and much more amenable to life for the creatures that rely on the river. We can only hope that in 2025, when the project is complete, that the restoration of the lower Moshassuck can begin ands the lower income communities along the lower river will start to see the benefits that have Come to the rest of the rest of the places that the Narraganset Bay Commission sewage system covers.

When Greg Gerritt was 14 years old...

...he read a book on endangered species and it set him on the course of a life's work on environmental causes.

His work has covered endangered species, forests, solar energy, local agriculture, compost, environmental justice, the Moshassuck river, and how to create a local economy focused on ecological healing and economic justice. About 10 years ago Gerritt was walking in Providence’s North Burial Ground and in a little wetland he came upon a school of little black tadpoles.

After visiting the tadpoles each spring for a couple of years he got a video camera and started recording

the growth and lifestyle of the tadpoles, created the Youtube channel moshassuckcritters:

named for the river that runs through the Burial Ground, and has been making short videos of all of the wild animals that live in the urban parts of

the Moshassuck River Watershed.

The first couple of years the focus was on the growth and lifecycle of Fowlers toads, including making the classic video of tadpole

development "6 Weeks in 90 Seconds" and after 4 or 5 years he became rather expert on their lifecycle, contributing

independent research to the Wikipedia article on their breeding cycle, and contributing a video to the Roger Williams Park natural history

museum exhibit on urban wildlife. But toads and tadpoles are only visible in the spring in Providence, so as he continued to record animals

all year round he branched out into turtles (there are both painted turtles and snapping turtles in the NBG), the three kinds of herons that

regularly visit the NBG, songbirds, hawks, bats, muskrat, coyotes, and the fish that fill the downtown rivers each fall. And during the time of

the COVID-19 pandemic, with the North Burial Ground closed, he has been making videos of Osprey in an industrial area of Pawtucket

along the Moshassuck River.

Beyond his own videos, Gerritt has been interested in who else is making videos of wild animals in Rhode Island, so he pulled together a

partnership of the Environment Council of Rhode Island and the RI Natural History Survey to put on the

Rhode Island Nature Video Festival this past February at URI. About 20 video makers in RI, from those who made cellphone videos of a chance occurrence while

hiking to professional video makers submitted videos. About 130 people attended and it is likely to be an annual event from now on.

source: Doug Victor's May Newsletter

Rainwater Pool Provides Vital Amphibian Habitat at Providence's North Burial Ground

Rhode Island Green Infrastructure Coalition October 2020 Newsletter

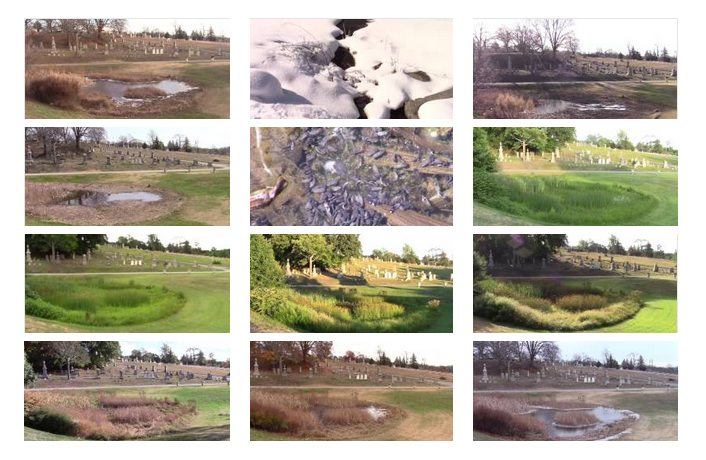

About ten years ago, Greg Gerritt, the watershed steward for Friends of the Moshassuck found a population of Fowler’s Toad tadpoles in a small rainwater fed wetland in Providence’s North Burial Ground. He has watched, studied, and filmed them ever since in an effort to understand the ecosystem of the rainwater pool and the creatures that inhabit it.

Years of study and observation led to an understanding that the pool collected all of the stormwater runoff from the area and that it held water for 3 weeks. It would continue to stay relatively full if each week it received at least .9 inches of rain in no more than 2 storms. It takes nearly a half inch of rain to work through the obstacles and runoff into the pool.

The vegetation at the pool is changing rapidly, with cattails squeezing out nearly everything else and the pool is rapidly filling in with silt carried in from the watershed during storms. Research also showed that this was probably the only population of Fowler’s toads in the city with no records of Fowler’s Toads anywhere in the city in the last 100 years.

Amphibians are the most endangered taxa among the vertebrates, with extinctions rampant. Many amphibians are dependent upon wetlands, which are also endangered. The goal of the Green Infrastructure Coalition (of which Friends of the Moshassuck is a member) is to clean stormwater before it reaches critical parts of the ecosystem, so it made sense to try to use the cleaner water to restore and enhance the amphibian habitat.

The Rainwater Pool became a study site and eventually a restoration site, in which it was proposed that the center of the pool be deepened to provide a few additional days before the pool went dry in a dry breeding season.

In 2018, Friends of the Moshassuck did a small excavation deepening the pool about 6 inches over a 10’ x 25’ area in the center - in partnership with the Providence Parks Department and with a permit from the RIDEM.

2020 has been a dry year, as of September much of New England, and Rhode Island, have been declared to be in drought, and in fact the rainwater pool has been dry most of the summer, and for the first time since the study began, absolutely no tadpoles turned into little toads and hopped away. But as 2020 was the first drought since the pool had been deepened, it was the first time we could observe how well it worked. It is one of those situations in which you can say the operation was a success - but the patient died.

The pool does now hold water for an additional 4 days as predicted, and twice this year the extra water preserved tadpoles through a few days beyond when they would have survived. However, eventually the pool went completely dry and all of the tadpoles perished.

There are very limited sites in RI where it would be appropriate to enhance or create amphibian habitat while managing stormwater. It takes a special site, but the work FOTM did on the topic has influenced people working with spadefoot toads to create habitat, though not in places where it is part of stormwater management.

Friends of the Moshassuck has a YouTube channel, MoshassuckCritters, which documented the entire process and project.

Please check it out to learn about these tadpoles and other critters!

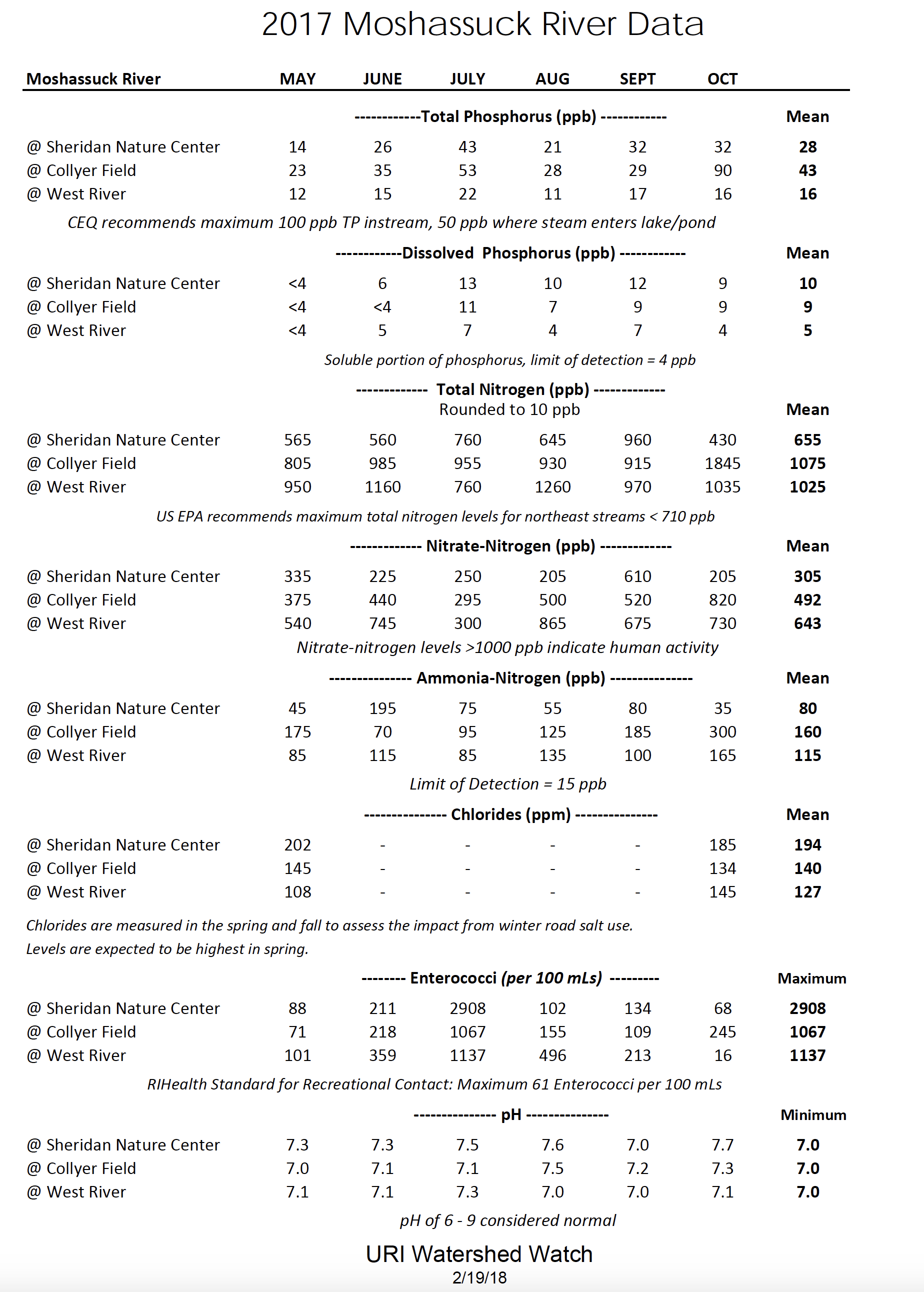

Participating in Rhode Island Rivers Water Testing

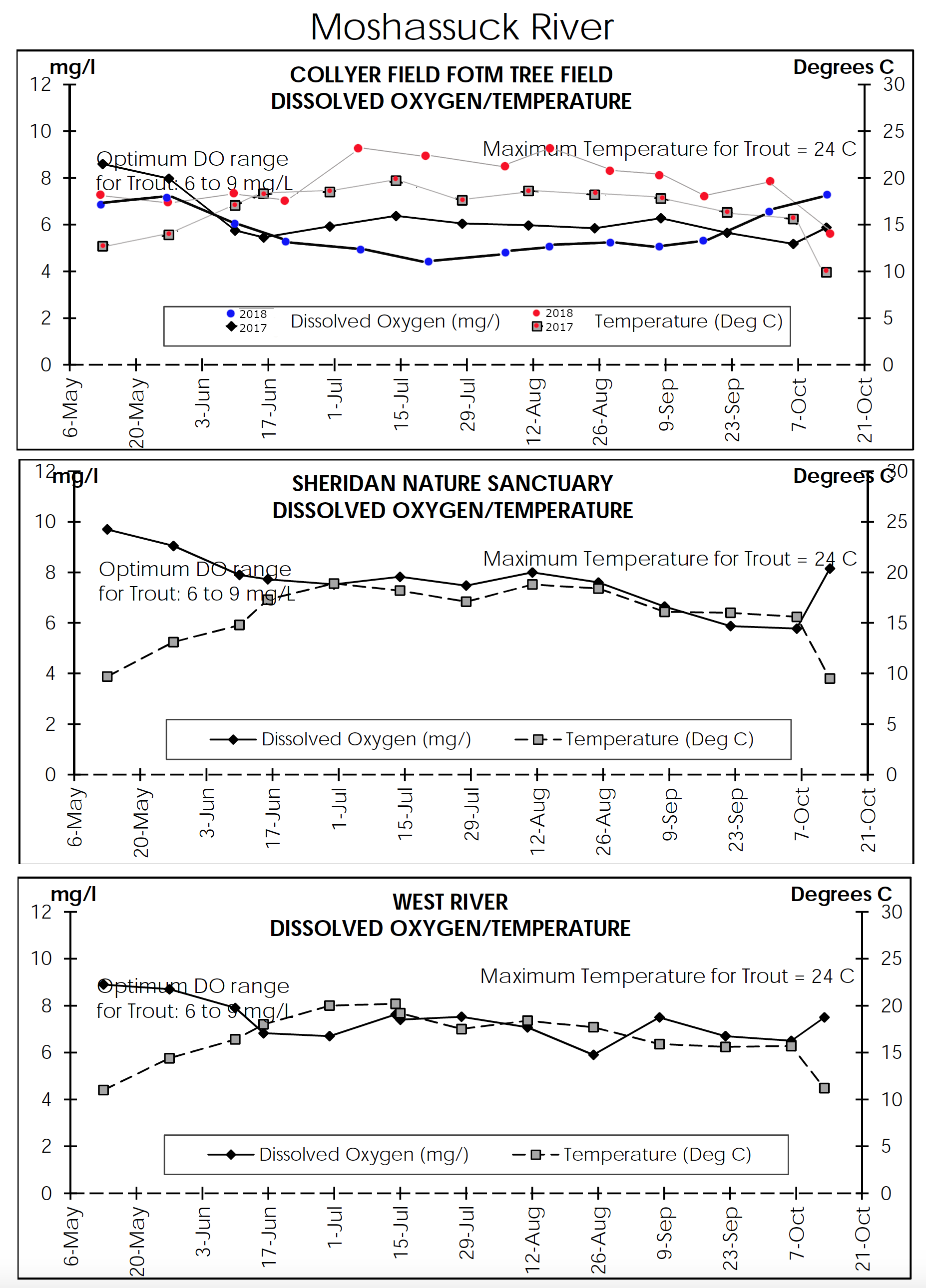

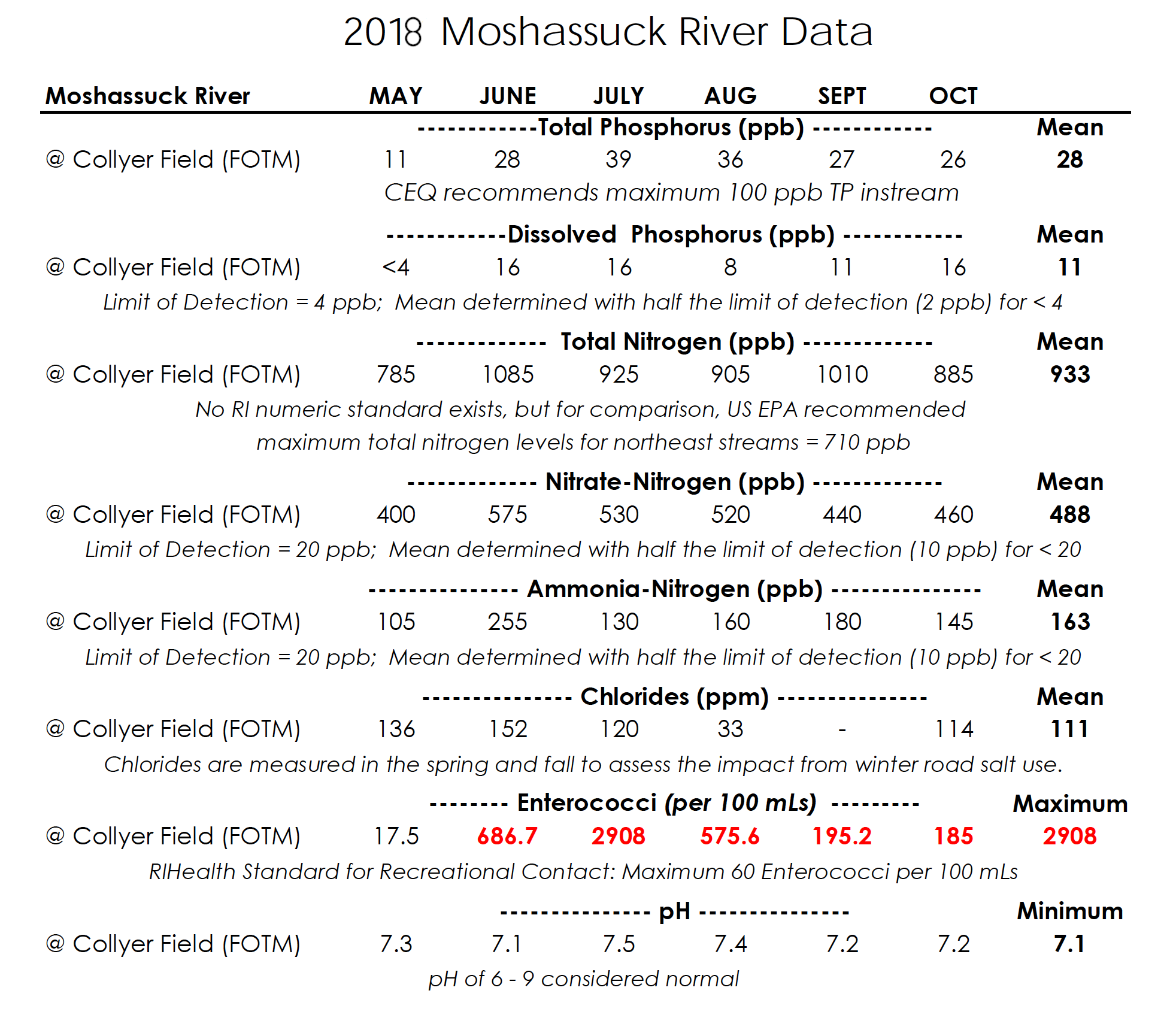

Sometimes data tells a story. FOTM participated in the annual URI Watershed Watch river water quality testing program in 2017 and 2018. The data gave us a good sense of the health of the river for fish and we will participate again in the future to compare with the baseline results below...

Greg Gerritt's Submission to the RIDEM Wetlands Restoration Team

The North Burial Ground a 300 year old cemetery along North Main Street in Providence has a small wetland that is fed entirely by the runoff coming from a small watershed that funnels water down 3 roads to the rainwater pool. The pool is in an area that would have been originally part of the wetlands lining the Moshassuck River, but between 300+ years of civilization, and the reshaping the area due to the Blackstone Canal and I-95, the river runs underground, and it is hard to say what is natural and what is not. I have been told that in the past the pond was deeper, more permanent, and had a fountain. The 2016 Rainwater pool video series provides detailed pictures of the site, but I am including aerial photos from google as well as screen shots from videos showing the pond. Currently the pool is completely dependent upon rainwater and the pond levels go up and down pretty consistently with the rains.

I was first attracted to the pool in 2011 when I noticed black tadpoles one spring day. In 2013 the Moshassuckcritters video project of Friends of the Moshassuck started documenting the tadpoles and other NBG wildlife. As I spent more time at the pool and watched it change across the seasons and years, I came to understand the pond as a rainwater system, and studied how the Fowler’s Toads and Gray Tree Frogs interacted with the pond.

The rainwater pool in the NBG is approximately 100 ft from east to west and 60 ft from north to south. The grass is mowed right to the edge of the wetland around most of the pond, with a steep sided section on the north covered in knotweed and vines. The pool is closely abutted on 2 sides by cemetery roads. To the south and west the land rises to the cemetery sand piles and a dirt road providing access to the piles off the route to the main gate. Land management practices around the pond create some erosion, but the dirt road, with its delta reaching on to the tarred road, is the source of most of the silt going into the pool, as silt deposits can be seen all the way from the delta to the pond. It seems like the pond has become shallower and vegetation has taken over more of the bottom of the pond recently.

Recent data suggests strongly that amphibian populations in New England are very dependent upon how long the hydroperiods are of ponds that do go dry and therefore have no fish. I believe that the shallowing of the rainwater pool is reducing its hydroperiod. Over the last few years I have watched the pond go dry with tadpoles in it, and then seen the toads and frogs try again when the rains returned. With a hydroperiod of between 12 and 14 days, and the need to have about an inch of rain each week to maintain water levels, it seems that if the hydroperiod could be extended by 4 to 7 days for a full pond, that it might provide for a much higher percentage of years in which breeding is successful and little toads and tree frogs hop away from the rainwater pool during the summer.

Amphibians

Amphibians, with the need for multiple habitats to complete their life cycles, are vulnerable, and even more vulnerable in civilization and during climate change. Amphibian populations and species are disappearing faster than any other large groups of species on the planet right now. The populations using the rainwater pool for breeding are the only Fowler’s Toad and Gray Tree Frog breeders noted in Providence for 100 years. I know of no other populations, though I know a variety of other amphibian species live in the city. Unlike some of the most vulnerable amphibians, Fowler’s Toads breed over a lengthy breeding season whenever conditions are right, and have further resilience in that they can have a breeding cycle interrupted by several dry weeks and start up again when the rains return. Gray Tree Frogs also breed at the pool over an extended season, but treefrog tadpoles are rarely seen, and only one year have I seen numerous shiny little green frogs come out of the pond. I know less of the conditions necessary for tree frogs, but at least one thing is clear. The pool needs to hold water longer for tree frogs to metamorphose as they mature a bit slower.

The rainwater pool is silting in, reducing the hydroperiod and increasing the odds that the amphibians using the pool will be unable to complete their life cycles. We propose a simple intervention that places essentially no risk on the amphibians using the pond by working on the pond in the off season and doing relatively small amounts of work in a way that simply lengthens the hydroperiod a bit by deepening the pool and possibly lining it so that it holds water better.

The work

The work entails removing 8 to 12 inches of silt from the deepest part of the pool, and smoothly tapering off until at the current edge of the pond the depth remains the same. We shall cut the cattails back about 5 feet and in the course of removing a few inches of sediment in the western part of the pond remove some of the pickerel weed. There is still some discussion among my collaborators as to how wide a swath should be included in the deepening of the western part of the pool. Several other plants with patchy distributions reside in that area. The cattails, pickerel weed, and other plants should return on their own as none of their patches will be completely removed.

No other vertebrates use the rainwater pool regularly, with ducks using it when it is very high and leaving as soon as it shrinks, though there are a variety of insects that use it as well as microscopic pond fauna. Doing the work in the off season, and only when the pool has gone dry will prevent most harm to the fauna.

There are some things that would be very good to know before moving any dirt. The first is a need to actually look at the soils in the bottom of the pool and understand their water holding capacity. It has been suggested to me that it is likely the soils are rather sandy, after all it is a burial ground, places chosen due to droughty soils that made for poor agriculture but easy digging. That might mean adding something to the bottom of the pool once the extra silt is removed, either a layer of clay or some sort of liner. First step is to get a professional to look at the soils.

The way the work could be done is with a crew of volunteers with shovels, possibly supplemented by something on the order of a bobcat for removal of cattails, and we are not removing much soil, probably an area of 30 by 50 and no more than a foot deep at the most, and much less most places as it slopes to the current shoreline.

About two inches of the top layer of pond bottom should be removed and kept separately. When done this should be returned to the pond to seed flora and fauna. If the soil has sufficient water holding capacity, then simply deepening the deepest hole by 8 to 12 inches and sloping it smoothly to the shoreline will be sufficient. If the soils are not tight enough, it will mean digging a bit deeper to put in some sort of impermeable layer and then backfilling to a depth 8 to 12 inches deeper than the current situation.

Friends of the Moshassuck is a regular partner with the City of Providence Parks Department on this and other sites in the watershed. The city is most willing to let FOTM do this project and believes that the project should simply be considered routine maintenance of rainwater infrastructure. It is likely that the actual work will be done by a crew of volunteers with shovels and wheelbarrows, though we are not currently ruling out using small motorized digging machinery to remove the cattails.

It has also been suggested that some sort of silt filter be installed where the rainwater funnels into the pool basin in the northeast corner. That is a project for another year.

A Project of the Environment Council of Rhode Island

The Green Infrastructure Coalition is interested in the idea of creating amphibian habitat in those places where it makes sense and to include this in the standard manual of practices for increasing resilience in our communities. Friends of the Moshassuck is pushing the envelope.

Beyond simply preventing flooding,and reducing pollution in our waters, it also behooves us to find beneficial ways to use our cleaner storm water and improve community resilience. One use for this water could be as breeding habitat for amphibians such as frogs, toads, and salamanders. Amphibians are a bellwether. They tell us if our community is healthy as they are sensitive and need a variety of habitats to insure their survival. In the North Burial Ground runoff from 3 roads ends up in a depression that can hold water or a week or 4 months, depending upon how much it rains. Fowler’s Toads and Gray Tree Frogs breed there. I have seen toadlets the last 5 years. But due to siltation from upstream, it is filling in fast and changing its characteristics. If it fills in too much it will not hold water long enough most years for metamorphosis to take place.

In some ways this is routine maintenance, but as it has never been done, I am engaged in a discussion with the various authorities about what to do and how to do it. With the understanding that there are other places in Rhode island and beyond, which might be able to use stormwater to aid amphibians, and therefore we need to think carefully about regulations and see if they can be a bit more amphibian friendly. Friends of the Moshassuck is partnering with the City of Providence on this, as the site is in a city burial ground. To explain and clearly demonstrate how the rainwater pool functions and what lives there, I am producing a series of short (2 to 5 minutes) that show the ups and downs of the pool for each month of a year. Beyond education, one of the purposes of the video series is to have evidence available so that RIDEM can decide what is proper at the site, And then hopefully to document the work we do to keep amphibians hopping in Providence.

See: the story online on http://www.greeninfrastructureri.org

Scott Turner, Providence Journal

Constantly in motion, hundreds of roundish black tadpoles, between the size of a pea and a rice grain, circled the outer ring of pond water clockwise in the early morning sunshine.

When the sun reached its zenith at noon, so would the tadpole numbers, with thousands of the little amphibians zipping around the water’s edge, said Greg Gerritt, founder of the Friends of the Moshassuck and author of the Prosperity for Rhode Island blog.

Seemingly always on the move, as well, Gerritt walks wherever he needs to go. In doing so he observes changes in the landscape big and small over the years, including the ebb and flow of this little pond and the gray tree frogs that breed in and around it.

“Rise and fall of the pond is based strictly on the runoff it gets and how fast it evaporates,” Gerritt said. Watching the tadpoles each spring, he added, brings “a renewed sense of wonder, as they populate the shorelines by the thousands.”

Only about two inches long, gray tree frogs live in wet woods or swamps. They need temporary pools or permanent water for breeding.

When the pond shows up each spring, male gray tree frogs gather in adjacent trees and began calling, mostly at night. The males produce a loud trill that lasts between one and three seconds.

Then the frogs meet at the pond to mate. Females select males, based on their calls. “They are creatures of song,” Gerritt said.

They are also a lesson in flexibility.

In 2012, rains began to fill the little pond on April 25, he said. The first tadpoles appeared May 12.

This year, the pond went dry on April 25. After it filled somewhat on May 10, the gray tree frogs began calling, but the pond went dry on May 20.

The pond reappeared on May 25, with the rains of early June sending it well over its banks. The frogs began calling, and then gathered to breed. The females laid thousands of eggs, and tadpoles emerged four to five days later. In two months, they will have changed into frogs.

Worldwide, biologists report vanishing amphibian populations. Research published last May found that the average rate of decline for U.S. amphibians was about 3.7 percent a year, compounded over time.

The frogs also represent resilience and adaptability.

The gray tree frog tadpoles swim in a low spot of turf by a maintenance shed in the North Burial Ground in Providence adjacent to Route 95. They scoot around the pond like cars that zip up and down the highway.

North Burial ground is home to more than beloved mothers, fathers and children of Rhode Island. A larger, more permanent pond in the cemetery, for example, harbors turtles, bullfrogs, fish, great blue herons and more.

This year, Gerritt and other members of the Friends are videotaping wildlife in both ponds, posting the recordings under “moshassuckcritters” on YouTube.

One evening at the little pond, Gerritt said, frog calls intensified strikingly with each minute of encroaching darkness. Another night, this time at the bigger pond, he looked up from recording to witness the ghostly shadow of a black-crowned night heron hunting at the edge of the pond under the moonshine.

When a seasonal pond retracts, tadpoles must move inward, or die. In the morning sun, we found a small pile of the gray tree frog tadpoles glistening at the drainage-ditch canal that feeds the pond. They didn’t make it, but they did provide food for a small mammal that left fresh prints in the mud overnight.

Gerritt wonders whether gray tree frogs breed anywhere else in Providence, given that they live in forests and require temporary pools of water to mate.

“When 20 or 30 frogs are calling, from the ponds, from the trees all around the pond, it is not only a sonic experience, it is a visceral one,” he said.

“It may be the most addicting thing I know. I get out there and just want to record and listen all evening.”

Scott Turner’s (scottturnerster@gmail.com) nature column appears here most Saturdays.

By FRANK CARINI/ecoRI staff San Francisco has instituted a mandatory three-bin system for the collection of trash, recyclables and compostables.There’s a movement afoot to bring curbside composting to Rhode Island.

San Francisco has instituted a mandatory three-bin system for the collection of trash, recyclables and compostables.There’s a movement afoot to bring curbside composting to Rhode Island.

The Providence Urban Agriculture Task Force and the Environment Council of Rhode Island were awarded a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) grant to find out how to remove food waste from the Ocean State’s trash stream and use it to create organic soil rich in nutrients.

Greg Gerritt, a member of the Environment Council of Rhode Island and a vocal environmentalist, is spearheading the effort. The Providence resident has spoken to dozens of people about the idea in hopes of developing a plan that meets the needs of municipalities, farmers and gardeners, among others.

Gerritt has organized an invitation-only meeting for Jan. 15 at The Rhode Island Foundation, in which stakeholders will exchange ideas about curbside composting and the various facilities that would be needed to support it — from an agricultural model to an industrial model to the use of greenhouses.

The meeting will include lawmakers and representatives from various Rhode Island cities and towns, restaurants, local colleges and universities, waste haulers and the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation.

“We want to see who is really interested and who might have resources to bring to the table,” Gerritt said. “Back when I began looking at this issue, I thought the hard part would be to develop a collection system. I now believe that is totally doable, and now I believe the key factor will be to determine what type of facility or facilities to develop and then figure out how to find the money, find the partners, find the investors.”

Compost is a mixture of decaying organic matter, such as potato skins, coffee grounds, carrot peelings and apple cores, used to improve soil structure and provide nutrients. Unfortunately, most of Rhode Island’s valuable food waste ends up buried in the ever-shrinking Central Landfill.

The USDA estimates that nearly 26 million tons of annual food waste ends up rotting in landfills or being burned in incinerators. Food waste that doesn’t end up buried or burned, is chewed up in garbage disposals, which increases the load on sewage treatment plants, wastes water and keeps more nutrient-rich food scraps from being used as fertilizer.

In fact, less than 2 percent of U.S. food waste is managed through composting, according to the federal agency.

“The Urban Agriculture Task Force does not have the ability to transform the management of waste in Rhode Island on its own,” Gerritt said. “The only way this transformation is possible is if all of the potential partners, all of the organizations that deal with our waste stream, realize composting is in the best interest of the community and economically feasible.”

Amelia Rose, lead organizer for the Environmental Justice League of Rhode Island, said it is imperative that “we reduce the waste burden in Providence and throughout Rhode Island.”

She mentioned composting and recycling as the best ways to reduce the amount of waste unnecessarily being dumped at the state landfill in Johnston. “Structures are in place that encourage waste,” Rose said. “If we make recycling easier, make composting easier, people will do it.”

The organic matter that Americans discard daily, including food scraps, yard trimmings and other biodegradable garbage, comprises 23 percent of the U.S. waste stream, according Mike O’Connell, the executive director of the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation, which runs the Central Landfill.

He said Rhode Island needs a system that better keeps organic materials out of the landfill. “Organics are the next big pile of waste we will need to address,” O’Connell said. “We need a delivery system and we have to make sure the compost is clean.”

The tons of food waste Rhode Island buries annually could be better used to produce rich, black compost, or the appropriate food scraps could be used to feed farm animals.

To make better use of nutrient-rich organic matter that often is being needlessly tossed out with the trash, curbside composting programs are being initiated across the country. Inspired by San Francisco, which was the first city to institute a composting program, other cities with roughly the same population as Rhode Island, such as Seattle and Austin, Texas, have established similar programs.

Other smaller cities, such as Boulder, Colo., Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minn., Rapid City, S.D., and Berkeley, Calif., facing a decline in available landfill space and understanding the wastefulness of burying valuable organic material also have implemented some type of curbside composting program.

Compost improves the constitution of soil by making it more able to contain air and water and resist erosion. It also provides nutrients for plant growth and increases storage of carbon.

“Good compost changes dirt into rich, organic soil,” Gerritt said. “You put the seeds in and the plants jump out.”

For more information, contact Greg Gerritt via e-mail at environmentcouncil@earthlink.net.

By Scott Turner Oct. 17, 2009 in the Providence Journal

When I needed a place to “chill” during childhood I snuck into a nearby garage, snuggled in my own thoughts and dozed off.

I think of that oasis when I visit the Moshassuck River. Cool, damp, serene, sometimes smelling of oil and gas, home to Roger Williams and the Industrial Revolution, it’s the “river where moose watered” long ago.

The Moshassuck, with its beginnings in the tiny streams of Lime Rock near Lincoln, slices through a valley once the natural course of the Blackstone River until ice jammed it eons ago. Look west from College Hill to the 180-foot summit of Windmill Hill to witness the Moshassuck’s natural corridor.

It is "an old, old path," said Greg Gerritt, founder of Friends of the Moshassuck, an advocacy, protection and restoration group. The valley was a main line before, during, and after the Revolution, when manufacturing was king in Rhode Island, and the river served as industrial sewer for mills, metal works and textile factories.

Today the Moshassuck shares the valley with hundreds of home and commercial properties, and major routes, including Interstate 95, Amtrak and MBTA rail lines, and North Main Street. At least 29 roadways cross the river across several communities.

Last week, I ran into Gerritt on my way to the river. We walked over to Collyer Park. Although the whine of interstate traffic dominated, I could still hear the water rippling over fallen trees.

We stood under a red maple on the stonework of the channeled bank. Sunlight pierced the crimson foliage, illuminating the river bottom. The summer algae and sewage smell were gone.

Gerritt said that in about 10 years, completion of the Narragansett Bay Commission’s combined sewage project would finally rid the Moshassuck of human waste.

In Collyer Park, Friends of Moshassuck have transformed a field of invasive Japanese knotweed into a budding river bottom forest of red and silver maple, sweetgum, red oak, river birch and white ash. The trees produce shade that suppresses the knotweed.

Japanese knotweed spreads rapidly into dense thickets, particularly along shorelines, withstanding drought, and flooding and high heat. It can reach 10 feet in height, with broad, oval pointy tipped leaves.

I’ve watched the trees planted by the Friends spread from atolls into a growing riparian forest, and the knotweed underneath begin to whither.

A trail of thick black plastic, dotted with the lemon-yellow land snails that congregate on it, winds through the new forest, which produces a fruit cereal display of gold, orange, red, purple and yellow in late October.

When a train in the valley discharged a three-second wistful warning whistle, I thought of our restructuring world in which so many people live in constant fear and uncertainty.

Restoring the health of local environments is a way to repair the world, Gerritt said. "If we don’t heal ecosystems, we won’t make it on this planet."

Once, the Moshassuck fueled the greatest nation on earth. Then the river was left to die.

Still, the not-always-pretty Moshassuck flows to the sea. From its banks, Gerritt has seen menhaden, suckers and sunfish, fox, muskrat and herons.

Repair work by the Friends of the Moshassuck reminds me that mending can take a long time.

It was dark in the garage, where I once found refuge. There is light along the banks of the river, where a group of people believe they can transform the survival of an individual resource into a meaningful community for all of us.

Published by ABC Clio

The Industrial Revolution in North America began in Rhode Island with the construction of Slater Mill, the first mechanized spinning mill in North America, in Pawtucket in 1793. To power the mill Samuel Slater and John Brown built a dam across the first falls of the Blackstone River. Fishermen rioted when the dam blocked the fish runs up the river by salmon and shad and destroyed their livelihood. The federal courts ruled for the mill owners, here and in every contested case of damming rivers for the next 40 years (Jones 1992). Rhode Island became one of the industrial powerhouses of the world. By 1900 every creek had a dam and a mill at every place you could get 6 foot of head of falling water to power machinery. The Blackstone River and its valley, soon to be a National Park celebrating the mills, their communities, and the rebirth of the living river, had more than 1000 mills along its 45 miles, and other rivers in Rhode Island were nearly as densely industrialized. The textile industry gave rise to metal fabrication industries and the jewelry industry with their attendant pollution. The dyeing industry had the rivers running whatever color was hot in New York that year. Sediments in Rhode Island rivers carry a toxic legacy. The receding industrial tide left Rhode Island with many abandoned mills and an abundance of superfund sites.

The flip side is that Rhode Islanders love Narragansett Bay. It is the heart of the state, a water body surrounded by the state. It supports a huge tourism economy of swimming, surfing, fishing, sailing, dining, and has been at the heart of the development of tourism as an industry since Newport became home to the Mansions of New York Society in the later years of the 19th Century. The maritime industries have also been a powerful force in Rhode Island, with trade helping create many of the early fortunes, and commercial waterfronts and the fishing industry continuing to be a source of community prosperity.

Rhode Island has always had birders, beach lovers, preservers of open space and builders of parks. But like most of the country, environmental activism and efforts to “green” the community sprouted around 1970. Republican Governor John Chafee instituted the first public bonds for open space with the support of The Nature Conservancy and Audubon Society of RI. Struggles over the development on Narragansett Bay lead directly to the founding of Save The Bay, which has developed into the largest environmental advocacy and education organization in the state. A cast of hundreds “Zapped the Blackstone” in 1972, and in conjunction with the demise of the textile industry and the passage of the Clean Water Act the restoration of the Blackstone River had begun. Fast forward 39 years, and now, beyond the Blackstone, the watershed councils, federal, state, and local governments, and Narragansett Bay Estuaries Program are celebrating dam removals and the restoration of fish passages closed since the 18th century on the Pawtuxet, Pawcatuck, Woonasquatucket, and Ten Mile Rivers.

Rhode Island waters

Rhode Island has embraced the watershed approach. State agencies, municipalities, and the non-profit community increasingly see Rhode island as a series of watersheds and plan accordingly. With large point source polluters like factories cleaned up, the attention is now on controlling road run off, creating public access, and restoring habitat.

The Narragansett Bay Commission recently completed phase one of the Combined Sewer Overflow project and already swimming beaches are open more and shellfish beds can be harvested sooner after it rains because so much polluted runoff has been captured for treatment. When phases two and three are finished 98 percent of the overflows will be captured and treated before going into the rivers and bay. Eel grass, salt marsh, and shellfish restoration is going on throughout the bay. Inland, dam removals, the building of fish ladders, and other work, is restoring riverine habitat and it is estimated that several hundred thousand shad and herring will return to RI rivers for spawning in the next few years. Every river and pond now has a friends group working for its restoration.

While Rhode Island is making progress restoring water quality and habitat, there are issues with quantity. Watering lawns is such a large drain on aquifers that some of the smaller rivers are going dry for parts of the summer in drier years. Efforts to reduce lawn watering through better horticultural practices including planting for hardiness is catching on, but mandatory restrictions on watering are occasionally used to keep rivers from drying up.

Environmental Justice

Rhode Island once had some of the highest lead poisoning rates in the country, though concerted efforts and lawsuits have dramatically reduced the rate. Several years ago the City of Providence built a school on the former city landfill and another on a superfund site that had once been a silver manufacturing company, the Gorham site. Jointly these struggles spurred the development of the environmental justice movement in Rhode Island. Work on school siting, brownfield restoration, community gardens, food deserts and security, lead, and bad air quality all continue to move forward. Progress at the legislature is slow. A bill introduced in 2011 to prevent schools from being built on sites polluted with Volatile Organic Compounds did not pass. Progress has also been slow on rules for making sure low income and minority communities are notified and protected in the permitting of redevelopment on brownfields. Regulations have been written and debated publicly, but not finalized.

The changing demographics of Rhode Island and especially urban Rhode Island mean that justice and community development have become the heart of environmental action. In recent polls Hispanic voters were much more likely to favor strong environmental policies than other voters (Sahagun 2010), and the green movement is changing to better serve the only growing populations in the state. The Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council has been a positive force for change in the poorest neighborhood in the state and the Urban Pond Procession marches fish parades through the streets to focus attention on the rejuvenation of ponds in Providence. Rhode Island voters continue to overwhelmingly support bonds for preserving land and cleaning up our waters, and new outreach into low income and minority communities will continue that track record.

Green Jobs and Green Energy, Mass Transit

Rhode Island has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country and the government and corporate sectors are unable to develop a workable strategy for economic revitalization. As a result a new paradigm is evolving of economic development being dependent upon ecological healing. An awareness is building that the way forward economically in Rhode Island is to heal our ecosystems, clean our energy systems, and grow our own food. Job training programs in green technologies and techniques have sprouted, but the new jobs are few and far between. It will take a more radical greening, a real healing of ecosystems; depaving streets, growing food and forests, taking down dams, and putting solar panels in the neighborhoods to break Rhode Island out of the doldrums.

The legislature did a pretty good job the last few years of passing legislation to mandate green energy in our electricity mix, and support off shore wind, energy efficiency, and green buildings. though the policies have yet to bear fruit, especially when compared to what is going on in neighboring states. Rhode island has become a leader in feed in tariffs for small scale generators of clean electricity. (Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources 2011)

Where Rhode Island has really fallen down is with mass transit. The Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) is primarily funded by the gasoline tax. This means that when gas prices go up and people drive less or drive more efficient vehicles, the amount of money available for subsidizing mass transit shrinks. At exactly the time when there are more riders and more need for the service the shrinking revenues force RIPTA to cut service and hours. In recent years the protests over transit cuts due to greater demand have become larger and more vocal. RIPTA and the legislature are well aware of the conundrum, but the legislature seems to be unwilling to actually fix the problem given all the budgetary constraints. (Environment Council of Rhode Island 2011) Air travel on the other hand seems to be on the favored list, for despite the objections of neighbors, in 2011 the Rhode Island Airport Corporation finalized plans to expand T.F. Green airport despite falling passenger numbers and amidst the growing realization that flying is returning to the status of a luxury due to high fuel costs fuel and climate change issues.

Offshore Wind

Rhode Island is a place of natural beauty, but few natural resources. But Rhode Island does have wind, and the effort to tap into the wind is moving forward. The state has a contract with Deepwater Wind to build an offshore wind farm, and the process is slowly grinding on. To facilitate the development of offshore wind the state’s Coastal Management Resource Council wrote the Strategic Area Management Plan (SAMP) for potential wind farm regions that is one of the finest examples in the country of coastal marine spatial planning. (Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council 2010) The document gives Rhode Island a reasonable start on finding the best sites to develop that would do the least harm to the environment and the people who make a living fishing. The state has also convened the Renewable Energy Siting Partnership a stakeholders group similar to that which created the SAMP to look at on shore wind, solar, and hydro power opportunities and -provide technical guidance to evaluate siting in municipalities.

This type of planning is critical. Already communities are passing laws to outlaw the building of wind turbines, so siting with great care must be done or else the whole state will be off limits to wind power. In the ocean it turns out that the continental shelf off of Rhode Island is among the most productive and biodiverse areas along the east coast and a hot spot for plankton, which attracts the sea turtles, whales, tuna, and other large sea creatures that are becoming progressively rarer. Knowing the hottest spots and planning to keep them healthy, will make this a much better process for all concerned.

Solid Waste

Rhode Island has a Central Landfill run by the quasi governmental agency the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation that serves 38 of the 39 communities in the state. It is closing in on its capacity, and in a small densely populated state, there are very places that one could fit a new landfill. It is also unlikely that any community would agree to become a sacrifice zone. It is generally agreed that the real solution is to produce much less trash. While Rhode Island was a recycling leader in the 1980’s recently the state has lagged behind. More and more communities are therefore implementing mandatory recycling, and the Central Landfill will soon be implementing single stream recycling. The legislature has passed a producer responsibility bill for certain kinds of electronic waste and some other products and Rhode Island is now in the process of implementing it. Rhode Island, unlike many of its neighbors, does not have a returnable bottle law. It shows up in the excessive litter through out the state, exacerbated by the near elimination of the state budget for litter control.

Rhode Island banned incinerators many years ago, though every year the incinerator industry tries to repeal the law. A better alternative is evolving in the movement to take all of the food scrap out of the waste stream so that it can be composted and returned to the land for growing more food. An anaerobic digester to capture methane and generate carbon neutral electricity from food scrap is set to open in 2013 and will go a long ways towards helping keep food scrap out of the landfill and returning fertility to the soil.

Agriculture and Land Use.

For 150 years Rhode Island was a place of mill villages fed by farms in the surrounding hinterlands. As the mills and farms disappeared the folks streamed out of the cities and created suburbs. Since World War Two the amount of land being used for housing increased nine times faster than the population grew. Pushed by Grow Smart Rhode Island the current thinking is to encourage redevelopment of the mill villages, town centers, and cities, taking advantage of existing infrastructure, while preserving the hinterlands for agriculture, forests, and other productive uses. Real estate development still drives politics, so it is difficult to make this cultural and economic shift, but some progress has been made. A housing driven recession has also slowed the suburbanization of rural Rhode Island. Land trusts and agricultural preservation programs are now found in nearly every town and have preserved for conservation and agriculture thousands of acres.

The one sector of the Rhode Island economy that is doing well is agriculture. The number of farms in the state has increased 42% in the last 10 years (USDA 2009), the number of farmers markets has quadrupled with nearly every town having at least one each week in the growing season, and the number of community gardens and gardeners has soared. Providence included in its comprehensive plan the right to grow vegetables in every type of zone in the city and has started developing community gardens in public parks.

Climate and Clean Air

What goes up in the air in the Midwest comes down in Rhode Island. Rhode Island is down wind of major cities and the electric power plants in coal mining states. It is an air pollution non attainment zone for Ozone. Asthma rates in the inner city are high. The compactness of Rhode Island means that drivers drive less than most Americans on, but Rhode Islanders make up for that by heating drafty old houses. Rhode Island is doing some of what it can, including helping people weatherize old houses, but clean air and the reduction of fossil fuel use and carbon dioxide emissions will take national and global solutions beyond what can be done locally.

Clean air and climate are inextricably linked as it is the combustion of fossil fuels that creates the air pollution, and the global weirding that we all see. Rhode Island has pretty good renewable energy standards in place, is taking action on energy efficiency, and approved using California CAFÉ standards. Maybe it is because Rhode Islanders know they are vulnerable to climate change and bad air quality. Rhode Island history includes some devastating hurricanes, but the floods of 2010 set records that underscored how older post industrial communities are increasingly vulnerable. In response the Rhode Island legislature created a Commission on Climate Adaptation. Rhode Island can do its share to reduce pollution by promoting green energy, and it is taking responsibility for reducing vulnerability to the changes that are already in motion. It is hoped that as the commission does its work it will explore actions that can simultaneously reduce Rhode Island’s carbon footprint, increase our community resilience, and help the state move forward economically.

Rhode Island is well positioned to contemplate global climate change. The University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography and other programs at local schools contain leading climate scientists who are engaged in the public debate The Coastal Resources Management Council has maps available that show what some of our communities would look like after sea level rises of three and five feet. (Coastal Resources Management Council 2008)

Conclusion

Rhode Islanders have a very strong environmental ethic. Translating that ethic into workable solutions to community problems in the 21st century will define how well Rhode Island weathers the storm.

CONTACT

FRIENDS OF THE MOSHASSUCK

37 Sixth Street

Providence, RI 02906

Telephone: 401-331-0529

Email: gerritt@mindspring.com